Monday 30th April 2018

Winter is making a final showing at Hougue Bie this week (we hope!) with low temperatures and a biting wind!

The volunteers are beyond worrying about the weather though and are cracking on with the tasks at hand!

The test daub sections we applied last time have dried completely which allows us to assess their qualities. What is noticeable is the hardness of the finished surface, where it has been finished smoothly it is hard to the touch and pretty resilient to knocks. The expected shrinkage is well within acceptable limits – with the widest cracks measuring between 1 and 3 mm. This suggests that we can try and squeeze more fibre into the final mixes to reduce this further, but it also depends on what kind of finish we might be putting on the walls at the very end. Narrow shrinkage cracks would actually act as a “key” to hold on a final render coat or even paint layer… Again, we have to start thinking about how the building will look when it is finished, now!

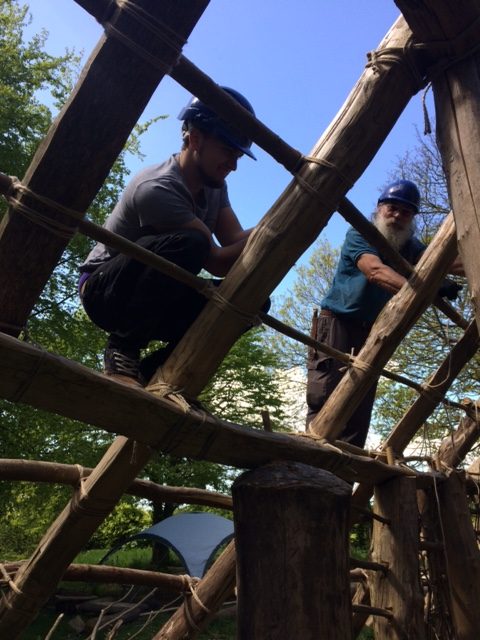

We are now well stocked with 4 mm hemp string for lashings, so the positioning of battens is proceeding this week. We are attaching the stripped (white) willow battens over the living space to give it a different appearance from inside.

Willow panels are continuing in preparation for a “Daub Fest” planned in July. We hope to get lots of visitors to help with this task during the first week of the summer holidays (July 23rd – 27th) so we can try and complete all of the daubing in a short space of time!

We are also boiling the next batches of willow bark for cordage. The new “Law” on site states that each volunteer should make a 28ft length of handmade rope for some of the critical lashings in the building. This is a serious task, requiring lots of prepared willow bark and time!

Tuesday 1st May 2018

The sun has unexpectedly come out to welcome the start of May! Finally, spring tries (again) to throw off its winter coat!

Today teams are continuing with the lashing of battens to the roof. We are aiming to finish one end of the building to allow thatching to start.

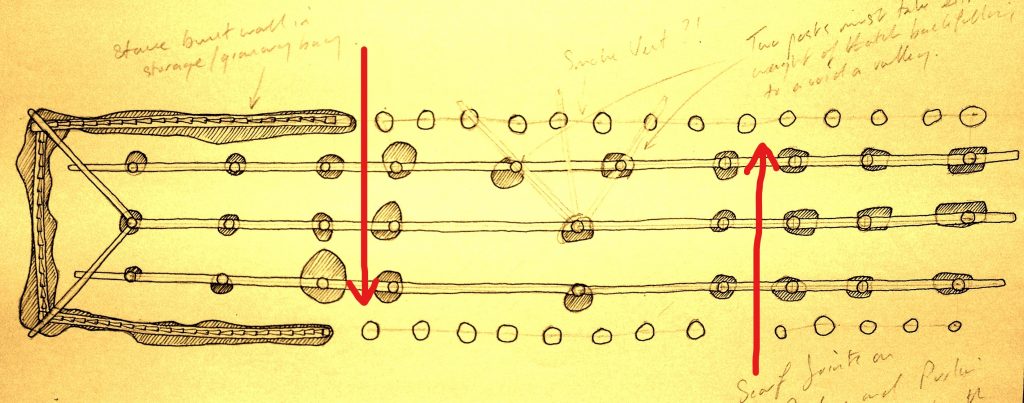

We have also made a decision on the mezzanine floors. We are now thinking that the passageways (see below) between the living space and storage and livestock areas should logically have floors that run over them. This would increase the floor area available to storage, and make use of the wasted full height space that would have been in a passageway used only for access to the other elements of the building. This of course assumes that they were passageways!

On this point we revisit the issues of reconstructing a building based mostly on ground evidence. It is interesting though, moving beyond the model and its constraints. As always, it is only at this stage that the reality of the building takes over. For the first time we can stand in the spaces and imagine how usable the finished building might be. Any doubts about the installation of a mezzanine floor have evaporated for me – simply because the structure is able to support one, and crucially, the space above the proposed floor is large and very practical. Any farming activities require large volumes of storage for tools, fodder and harvest crops and I don’t see how this building would support a farming economy without the use of floors that essentially increase floor area by 40%.

Kerry Jane has produced an amazing 17 ft (5.1 metres) of willow bark rope in just over an hour! She has changed the method to include tying the end of the rope to a post as she works – this makes it easier to maintain tension and to judge the thickness of the rope more accurately. What is also clear is the new preparation method of the bark is producing good quality raw material for the job. The long sheets of stripped bark (with the outer removed) are boiled for two hours in wood ash and then teased into narrow (5 mm) strips. These strips are then dried to keep them safe and soaked before use.

Wednesday 2nd May 2018

Rain is forecast for this morning but it is warmer than it has been!

This morning we have suspended work on the roof until conditions improve. The wet weather is ideal for rope making though as the rain keeps the prepared willow fibre moist while it is being twisted!

Danny is working on another willow panel on the south side of the building. The test daub panels have confirmed that we can use far less material than a traditional hurdle panel would need and still produce a strong and sturdy wall. There are of course any number of ways to fill a gap with willow rods, but our preferred method seems to use the least material for the strongest and neatest result. Horizontal spacing takes 5.5 metres of willow rod (12 rungs) whereas three verticals take 6 metres of willow rod (4 would possibly be better but use 8 metres of willow). – The horizontal method allows us to use any section from an irregular rod as they rarely exceed 50 cm in length, whereas the vertical rod method needs three 2 metre rods of higher quality (straightness) to ensure alignment. The gaps between horizontal rods ranges from 12 – 14 cm, while on the vertical method it ranges from 17 – 20 cm (requiring more infill material to achieve the same strength). There is also potentially an issue with the eventual finish – especially at the sides of the panel where the infill meets the post.

An advantage of the vertical method is the fact that the daub does not touch the ground – and the mini sill beam the vertical rods are housed in forms a natural dry course. This would be useful in particularly wet areas of construction. However, the evidence for these buildings seems to suggest a robber pit running close to the eave line (to take daub materials for the walls) and this would provide a natural drip trench for the eaves and a sink that takes water away from the wall bases.

Today a load of hazel was delivered to site. It was harvested by Alcindo and delivered by Dave Pittom – once again (and very kindly) using his sons scaffold truck. The hazel will be used for a range of tasks including roof battens, wall panels and floor panels.

28 Feet Later…

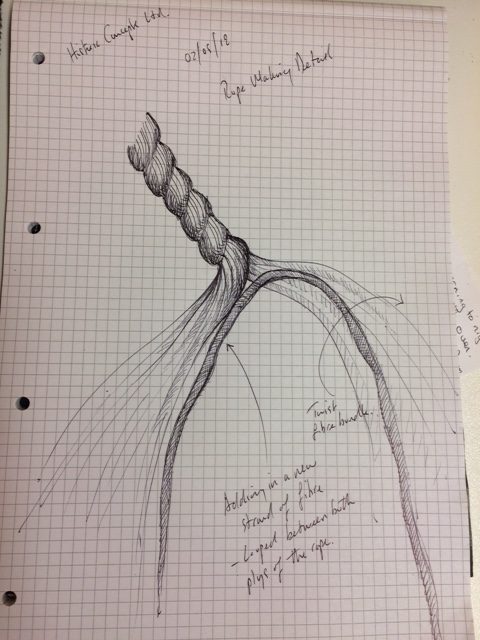

In the last two days, Astra and Edward have completed the first two 28ft (or 8.5 metre) lengths of willow bark rope! The length is what is required to lash a rafter to a purlin, wall plate or ridge. The process has been an interesting example of technological evolution – starting at a small scale and becoming more refined to produce larger quantities of material.

We have improved the outer bark stripping from using flint scrapers to split chestnut edges, we take the green outer bark off in stages and immediately peel the inner bark to stop it from drying out and adhering to the stem, and we split the sheets of boiled inner bark into 5 mm (roughly) wide strips as soon as it has been boiled as the fibres seem to separate easily at this point. Rope making is more efficient when the end of the made rope is tied to a post – this allows tension to be maintained, and the addition of more fibres is done by looping them across both rope ply – creating a strong join and allowing refinement in volume to be made.

Although we have found a method that works on the scale we need, I have no doubt that Neolithic rope makers would have taken the process many stages further to include detail such as precise willow species, the exact time of harvesting, the exact duration of boiling for best results, methods for splitting the boiled bark into fine fibres and a method of manufacture that would have produced large quantities in a shorter space of time. They also would have benefited from a direct line of knowledge transfer from their ancestors (undoubtedly over thousands of years), whereas we are trying, in many respects to re-invent that lost knowledge. Our rope production has been an interesting sideline to the main task of building a longhouse, but even the little we have done has hinted at the possible refinements we could make if we had the time to investigate and experiment fully.

Thursday 3rd May 2018

A long spell of dry and sunny weather has begun and our work on the roof of the longhouse can continue.

Teams are lashing more battens to the roof. The lattice of timbers is really starting to take shape – and the strength of the whole structure increases with every new piece of wood attached to it. Our decision to use stripped willow rods over the main hall is producing the desired effect – in combination with the more refined rafters, the roof of the main hall is already looking more refined than the other utilitarian aspects of the building.

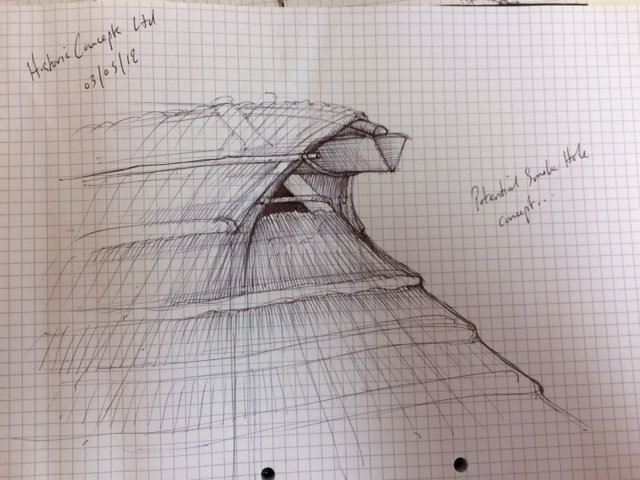

The “livestock” end of the roof is nearing completion and we now have to consider if some kind of smoke hole might be required. It is always easier to build a frame for one and not use it – than to retro-fit a frame once the roof is thatched.

The question of smoke escape in traditional roofs is an interesting one. Our familiarity with densely thatched (sometimes up to 45 cm thick) cottages belies the reality of thatched roofs before the advent of chimneys. A chimney takes smoke from the fire and delivers it beyond the roof line. This has led to increasing thickness in thatch since the medieval period – when, for the first time, thatchers had no need to consider the breath-ability of a roof – but only how long it would last. From experience, and without evidence for chimneys, ancient roofs must have had much thinner thatched roofs. The ability of a thatched roof in a pre-chimney building to breath is critical. Without a roof that allows smoke to escape, the living space rapidly becomes unlivable. Depending on the exact location of a house, its orientation, types of wood being burned, the size of the fire and the direction of prevailing winds, enabling an efficient draw (the movement of smoke out of the building) can be tricky and dependent on the through flow of air from doorways, windows or other openings. The heat of the fire is also critical to this fine balancing act. Too much air moving through a building will swirl the smoke into an unlivable haze, too little air will simply fill the building with smoke. For this project we intend to build in smoke holes and vents or openings in the walls. Only during a lengthy testing stage will we be able to discover which (if any) vents and holes are required to make the building work.

Friday 4th May 2018

The weather is fine again today… Another week is drawing to an end on the project. Everyone has commented that progress on the building is speeding up. This week we have achieved a great deal, and the roof frame is probably only one more project week from completion.

The next serious stage of construction will be the thatching of the roof. Before this can happen we reach a critical milestone in the project – the conversation between structural engineer and building control!

This building, although “ancient” and traditionally built, still has to be safe for visitors. This relies on the ability of a structural engineer to mathematically prove if the actual structure (as he sees it on the ground) will stand. My initial design has already been proven, and any changes we have made (due to actual materials) have been theoretically checked – but it is always an interesting stage – seeing the process of an ancient building being “ticked” off by professionals from the modern building industry. I suspect there will be a fair bit of chin rubbing involved!

Well done to all those involved this week! – a strange mixture of Winter and Summer weather was met with fortitude and achievement!