Monday 14th May 2018

This project week has begun with sunshine and a fresh breeze. The site has been transformed by the trees in full leaf, making the longhouse seemingly grow from the trees themselves. It nestles in its clearing so beautifully, with its natural lines mimicking the surrounding woodland shapes.

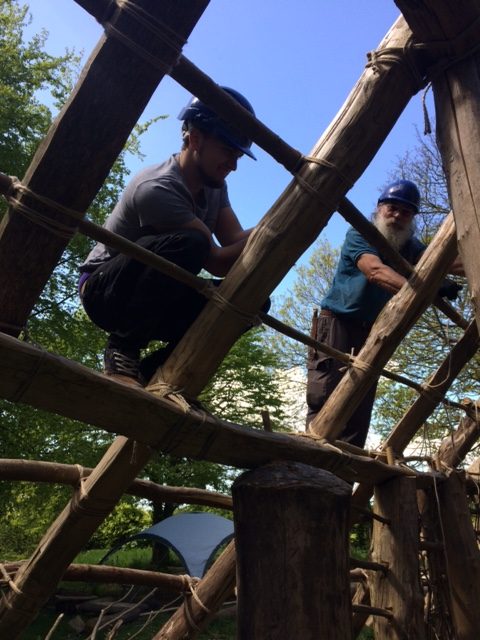

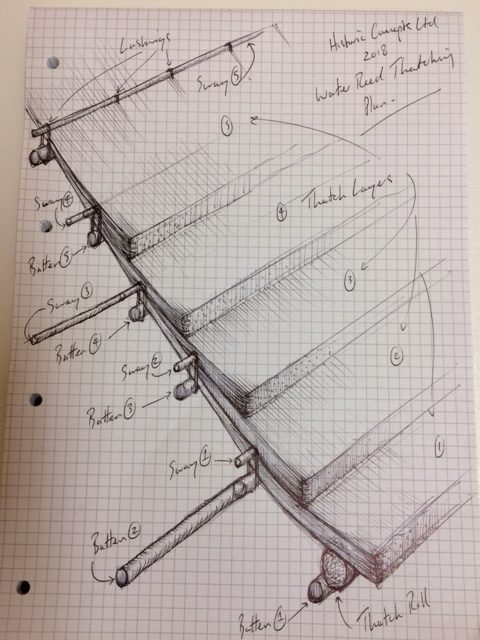

This week work continues with the lashing of battens onto the rafters to form the final structural elements of the roof. When this stage is complete we will have an all too brief view of the complete frame, the “skeleton” of the building, that will soon be lost, covered by the layers of thatch that will turn the project from beautiful frame into a useable building.

Although the thatch is an inevitable part of the build and has a beauty of its own, for me, the bare bones of a finished frame has a certain appeal that tells the story of how the building stands – and is visible reminder and physical story of the sheer effort and many processes that made it happen!

Derek and Danny are making a couple of final adjustments to rafters to ensure their ends don’t kick out too much from the wall plate. Although the roof will become an organically irregular shape, we need to avoid the creation of gullies that will naturally funnel rain water into them (keeping them wet and rotting the thatch). These final touches will make the difference between a beautifully functional roof and one that leaks!

Tuesday 15th May 2018

The sun is shining again today and a warmer summer breeze is welcome on site.

The battens on the south side of the roof are now finished! Nicky and Ruth are checking them all to ensure they are tight before thatching begins. The north side is ¾ finished with Astra, Ed, David and Derek lashing on battens and adjusting a couple of rafters to improve the shape of the finished roof.

Franco, James and Danny have made a start on the internal walls – the walls that divide some of the internal spaces such as the passageways from the main hall and livestock area. This “simple” operation uses the same method as building the willow frames for the external walls but it has inevitably led to a debate concerning the angle of walls. The simple question is…. “Do we join the dots (in terms of making internal walls by simply linking vertical posts) or fabricate more recognisable angles”? For now we have decided to join the dots and then see what spaces are available to us… it may be that we have to come up with some interesting storage solutions and carpentry, but the alternative is to make things straight in an organic building in order to fit our modern notions of usable space. We come back once again to the lack of detailed evidence for building interiors – and the eternal issues of building function reflecting material shapes and properties or the conscious decision making process and design of its occupants. For example, do the stone built Neolithic houses at Skara Brae reflect a design choice of making curved internal corners, or a structural solution to building a cor-belled wall/roof out of un-cemented stone?

We have the same issue with our timber building. Do the shapes we see in the surviving post holes reflect a conscious design that raw material was shaped to fit, or did it result from the use of a specific suite of raw materials? In short, we will never truly know, and the temptation exists (often in academic thought) to throw the weight of personal opinion into one or other camp. I feel the answer may lie somewhere in between. Coming to the modern era, we can look at buildings as diverse as the “Shard” or St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Both buildings seem to represent free choice in design (the whim or vision of an architect), but the reality is very different! Each (indeed all) building is the result of vision and design, but that design is often predetermined by factors such as location, available construction plot size, the eventual purpose of the building, what the society in which it stands is trying to say about itself, and of course available budget (in time and materials). Once the design is settled, the real work begins, the endless modifications and sometimes dramatic changes imposed by the qualities of materials and the calculations of structural engineers, issues of time and shrinking budgets (impacting on materials). There is also a factor present in all aspects of what we do and build that we often overlook, Tradition. For 99.9% of the time, things look like they do because of what went before. Whether it be a restrained baroque style cathedral or monumental modernist skyscraper, all buildings reference in greater or lesser ways, the styles and conventions of what has gone before. The same has to be the case with a Neolithic longhouse. We presume that the design of these buildings incorporated the new requirements and architecture from a farming economy and blended them with existing construction styles (based on a hunter – gatherer lifestyle), architectural thought and cultural needs to create what we now recognise as the beginnings of sedentary house building. The details of those influential parameters are, for the time being, lost to us.

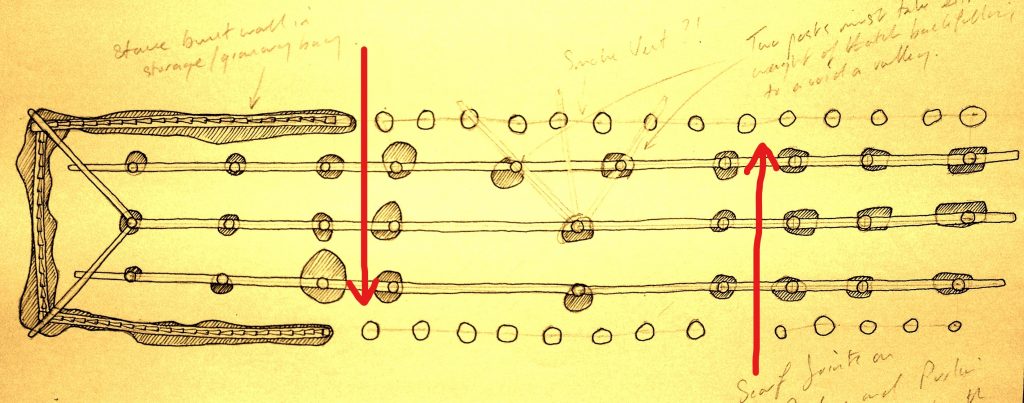

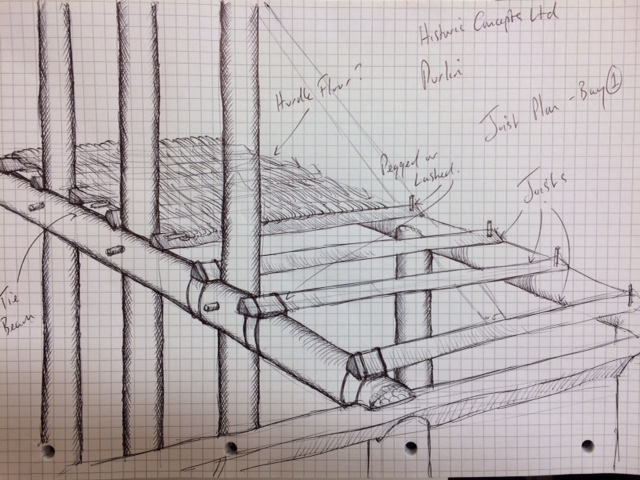

Today I have worked out the joist pattern for the 7 bays of the building (4 at livestock end and 3 at entrance end). We will require 56 joists varying in length from 1800 mm to 2200 mm. Each bay will have 8 joists that span from “tie beam” to “tie beam” – leaving gaps of 500 mm, which should be ample to support a strong floor (especially with a woven hurdle platform above).

Wednesday 16th May 2018

Today, work shifts from the roof to other tasks to allow unhindered access to the structural engineer and building control who are visiting today to check on progress.

The tasks include fitting the third layer of wall planks into the livestock end of the building. From the start, the evidence of a slot trench at this end of the structure inferred a different construction method to the rest of the building. Our interpretation has involved the setting of horizontal timbers in the ground (Sill Beams) and mortising posts into them to create upright walls. The gaps between posts are being filled with planks to create a robust wall that would be capable of protecting livestock from predators and also preventing their escape when being over wintered.

More willow and hazel needs to be woven into the finished wall frames in other areas of the building to create strength before we daub in July. And more work is needed on preparing the mezzanine floor joists before we begin fitting them in position.

Bob Godsell of “Just Structural” flew over from England this morning to check the progress so far. Bob is a structural engineer and has done the calculations for the building so far. It is always interesting to see how the structure lives up to what the model and drawings suggested. From the start of this project, the exact technical data has necessarily been a bit of a movable feast based on the exact decisions and specific pieces of timber we have used during the construction. Bob has now seen the structure and is more than happy with its strength. The interesting conversations now start with Building Control who determine if a building is safe based on the very latest measures from the modern building industry. On the face of it, a Neolithic Longhouse can never meet the requirements of a modern building industry – simply because it is using ancient methods. That does not mean that it is unsafe (as Bob’s calculations prove), but just different!

Thursday 17th May 2018

The fine weather is still with us!

Today we have a group of Corporate Volunteers with us from RBS International. Our “regulars” are showing them a range of jobs and processes to push the building onto the next stage.

Teams are busily working on draw knifing more joists for the mezzanine floors. Infilling the wattle panels with willow and hazel to make them strong, and tying on the few remaining battens on the north side of the roof.

Our new volunteers are very keen and hardworking, their efforts have made a real difference to the building in just one day!

What is interesting at this stage is the separation of interior space by some of the new interior walls. We are beginning to get a feel for the living space and the height of the mezzanine floor above the livestock bay. Interesting shapes are forming that force us to start thinking about the best way to “live” in the finished building.

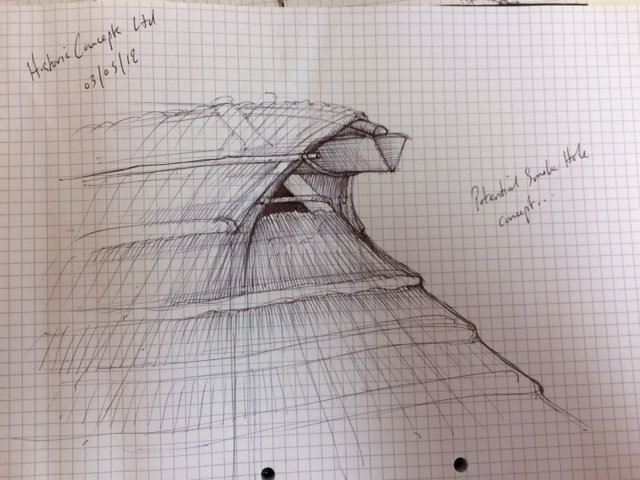

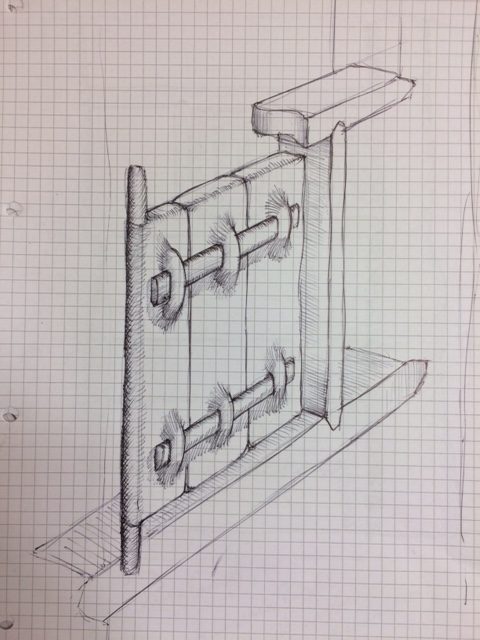

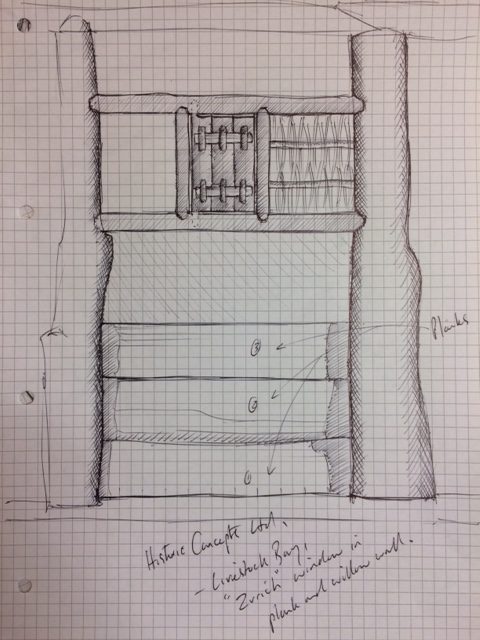

Today we made the decision to install some proper windows into the livestock bay walls. It has become apparent that this end of the building will be the darkest when the roof is thatched – only being accessed through two interior doors that open onto a single exterior door. To mirror the construction techniques in this bay (planks and sill beams), we are opting for a sophisticated solution. We will install two lintels or sills and two uprights to create a window frame. The surround will be planked or willow filled and daubed, and the window will be closed by way of a miniature Zurich Door (or window in this case) that will showcase the known carpentry skills of Neolithic builders..

Today, with the help of RBS International, volunteers gave 6895 minutes to the project – that’s nearly 115 hours! Well done all!

Friday 18th May 2018

A fine week is topped off with the best day yet! Warm sun and a slight breeze are filtering through the leafy canopy at La Hougue Bie. The Longhouse is partially hidden now by the summer trees and almost seems to grow out of the landscape itself. Birdsong is punctuated by the tap tap tap of wooden mallet on chisel or axe on wood.

Today, another good week of progress comes to an end. Tim and Mike have finished the batten lashings on the north side of the roof and are finishing by putting in willow or hazel rods between the crucks of the rafters. This final run of timber will give us options for attaching the thatched ridge at a later date.

Danny is working on another wall plank – the time consuming grooving of the upright is all too familiar now! Danny’s carrot is that when the third plank is in place, he will start making a sophisticated window to fit above it!

Iris and Astra are working together in “Bone Corner” – fitting a third plank – with bone chisels. Epic work especially in hard Holm Oak!…

Derek has begun the complex and detailed carpentry required to produce a “Zurich” style window. His logic is to produce the shutter first using off-cuts (we have limited splitting timber left) and to then fit the frame to the shutter – it will be interesting to see this marvel progress over the coming weeks.

Bill is also working on a third plank for another wall section while Heather, Ed, and Pippa are pressing on with the shaping of floor joists for the mezzanine floor at the livestock end of the building.

The progress of the building seems to be racing on now – and we are beginning to consider the detail of interior finishing that will be needed to turn this project from a fascinating construction into a home.